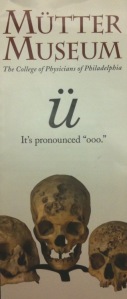

I had long heard of this museum, devoted to a 19th century medical teaching collection of models, skeletons, fluid specimens and the like. The abundant advertisements in Philly bill it as “Disturbingly Informative.” I am fascinated by anatomy, bones, art, the history of science…always been attracted to the unusual. As an undergrad I considered medical illustration as a career. But this place struck me all wrong. On a collections care level, things were dusty and most of the LED HOBO dataloggers seemed to have dead batteries. Exhibit design had a vaguely Vincent Price feel to it, with a wide mishmash of label styles, some including gothic font. Dark wood, polished brass and red/black color schemes predominate. I listened to some of the descriptions of forensic skeletal examination that could be dialed up on a cell phone, and thought those were quite good. But the professionalism of the recordings was at odds with the overall tone of the museum. It has a Coney Island freakshow feel to it, pandering to the titillating and weird, in a word: tawdry. In general, I don’t mind tawdry. Kitsch. Camp. Quirky. I’ve got several tattoos, including my wedding ring. One of my favorite bands is called “My Life With The Thrill Kill Kult.” If it were just the gruesome medical instruments and the detailed wax models of tissue diseases, this approach would not bother me. But it seems at least half of the collection is comprised of human remains. Skeletons, skulls, desiccated flayed children, babies in jars, preserved body parts, etc. Most of these people suffered considerably during their lives. Few consented directly to having their remains exhibited. Some labels describe prices paid for human remains. There is an extensive skull collection, and I saw one label describing a bone as removed from a grave in Hawaii. There is a lack of dignity in the interpretation of these remains. Culturally, intellectually, and personally I found the interpretation disappointing. My museum career as a conservator of ethnographic and archaeological objects involves a heightened awareness of the sensitivity of human remains, particularly issues surrounding the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. I am aware that many cultures, ethnic groups, and religions would consider any display of their human remains offensive. Most likely, some of those individuals are represented among the human remains on exhibit. Intellectually, I was disappointed that the exhibitions seemed directed at my visceral response to the collections and not my intellectual curiosity. Historical context, anatomy, and advances in medicine and forensics were not given the center stage that could legitimize the existence of such a museum. This museum is part of the College of Physicians, founded in 1787 as the oldest professional medical organization in the United States. It has a better story to tell than the one the current exhibition style is delivering. On a personal level, it was a little mortifying to think of my child in a jar, or how my grandmother would have felt having her breast on exhibit. For myself, I would be fine with having my own remains on exhibition. I would not even mind being in the Mütter Museum. I don’t have a sense that my own body is sacred. But out of respect for the inherent dignity of those deceased human beings in the Mütter Museum collection whose remains are on display, I wish the museum’s interpretive mission were more aligned with the mission of the College of Physicians:

The College of Physicians of Philadelphia advances the cause of health, and upholds the ideals and heritage of medicine.

The specific mission of the Mutter Museum is to collect, preserve and interpret medical collections in order to engender curiosity and knowledge about the body and health; to increase understanding of medicine in its cultural context.

A search of the internet revealed a major factor behind the interpretive tone of the museum: Gretchen Worden. She joined the staff in 1975 with a BA in physical anthropology, spending her entire career there. She became the director in 1988, and took visitation of a quiet 5000 per year to an impressive 60,000. She was much beloved in many quarters, and passed away in 2004.