You’d think you couldn’t lose something on the internet, but the blog post I did in 2009 for the Indianapolis Museum of Art’s blog no longer exists since they revamped their website. So here’s a draft, essentially the same thing but no pictures:

I go to the AIC annual meetings for one major reason: MORALE. I get excited, I get inspired, and my batteries get recharged. I go to a city I have never been to, agonize over attending talks tangentially related to my work or seeing museum exhibits I would otherwise never see. I spend time in a nice hotel chatting with people I really like and get to call it work time and collect per diem. I get to feel that I am part of a community. I like seeing the whole range of personalities…the really well dressed paintings folks on one end and the grungier ethno folks on the other. I like seeing the geeky nervousness of the grad students and try to reach out to them, remembering what it was like to be in their shoes and then feeling stupid when I realize they have more confidence than I did. I like seeing old mentors and giving them a hug and feeling the thrill that maybe, just maybe they think of me as a colleague now and approve of my work. Going to the talks is analagous to going to the movie theater when I could just rent on DVD. Humans like to roam in packs, and I love hearing a buzz go through a room when a provocative comment is made, or the titters of disapproval, or the nodding of heads with a good point, and I am excited when people are brave enough to ask questions after the talk and the sport of seeing how the speaker performs under pressure. Performance! Have you seen Arlen Hingebotham give a talk? Or Paul Messier? Or the NMAI folks giving a tongue-in-cheek Martha Stewart spoof chocked full of great tips?

2.0 definitely has its place. It can function in ways that AIC can’t or won’t. AIC has a hard time responding in a timely manner on current events and 2.0 folks can be the front lines for those opportunites for PR for our profession. I’m blogging for more personal reasons. Not long ago I saw a woman at the mall parking lot trying to wedge a child’s trampoline into her small car. I said, “Hey, it fits in my minivan…where do you live? I’ll drive it home for ya.” Sometimes you have the BE that nice stranger in order to have the community be the kind of place where you’re proud to live. I want to put content on my blog of the kind that I’d like to find. What if David Grattan had all his publications and notes and musings right there on the web? Or Nancy Odegaard? Or Tony Sigel? The web is now a place for (hopefully) useful stuff I generate but don’t plan to jump those those god-awful publishing hoops to share. I have published and I plan to continue to do so, but only a small percentage of what I am doing is unique or mature enough to bother.

I do see museums as the kind of place that is by nature slow and deliberative. Not designed to jump headlong into new things but rather hang back, observe, and help history sort itself out. AIC would have a hard time keeping up with Daniel Cull in terms of relevance anyway. Who runs AIC? How large is the staff and what can they reasonably get accomplished?? Manueverability is an unfair expectation of AIC. Should stick to the things it can do well…providing a platform instead of content. Free up the AIC website as a clearninghouse. Find a conservator. PA Fellow, Annual meeting. Nice to park useful stuff within an institutional structure to insure its survival.

Poster foreign language data aia

Weakness: who is attracted to this medium? Museum-L some of the most vociferous posters have some of the least reliable information.

Culture of exclusivity and elitism. Who is being kept out? Outside the tent pissing in or inside the tent pissing out?? What can MY blog do? Broader collaboration networks.

Tour: check out my blog

Marine mammal necropsy: check this project

Granting agency: here is this prototype

intern, this is what working with me would be like

People often come to museums to visit a specific artifact or collection they have a connection with.

People whose input you might really value are often not hanging out on their computers trolling the internet for places to contribute their expertise.

Closed email listserves…Museum-L.

I also really liked McCoy’s article. I’ve printed it out and left it on the breakroom table for my co-workers to read. (Funny, they are more likely to read it that way than if I send them a link…something about food and reading.) The Alaska State Museum where I work is in the process of determining how to merge the state museum, library, and archive into a future purpose-built structure. Discussions about areas of overlap & collaboration and ways to serve our constituents invariably come back to distance delivery and the opportunities of Web 2.0. From my five years experience as a curator at a small museum, I realized that many people visit museums to visit a specific artifact or collection they have a personal connection with. Not only is their information about that object potentially valuable to the institution, but in a healthy human animal there is a need to feel like a contributing member of society. Something about being inspired or connecting with big ideas stirs a desire in many people to be creative…to leave their mark…to be generous. However, that tendency can sometimes go awry. Museum-L for example. I have subscribed to that listserve for about 8 years now. Some of the most vociferous posters there have some of the least reliable information, but a huge desire to post. Some folks post there asking for information before doing even the most basic google search. But it is a window into the struggles of small-to-medium sized museums nationwide. I have cringed many times reading horrible conservation advice from non-conservators. But that forum is also where I met and formed my opinion about David Harvey, who can consistently be relied upon to gently correct misconceptions about conservation and steer receptive museum staff in the right direction, wrapping up with a chipper “Cheers! Dave.” I used to play a little game of “what would Dave say?” and usually I would agree with his assessment. Eventually I was able to meet him in person, but my opinion of him was fully formed virtually. I do believe Dave is a bit of an exception. There is a certain personality type who gravitates towards this medium, and I think we’ll see a plateau in the potential usefulness of 2.0 because there are folks whose input we’d really value, but they are busy doing other work and not online looking for places to contribute their expertise. And there will be legions of people who would love to share their opinion, but they don’t have the expertise to make it valuable.

Does AIC tick you off?

I can see why you hate AIC, but…

Rant on AIC, Elitism, and Blogs: Where is the Love?

Straight from Wikipedia: “Elitism is the belief or attitude that those individuals who are considered members of the elite—a select group of people with outstanding personal abilities, intellect, wealth, specialized training or experience, or other distinctive attributes—are those whose views on a matter are to be taken the most seriously or carry the most weight; whose views and/or actions are most likely to be constructive to society as a whole; or whose extraordinary skills, abilities or wisdom render them especially fit to govern.”

First things first: we need AIC and I respect the role it plays in our professionalism. You could say I was suckled at the AIC teat. Back in 1993, I was trying to find someone who would tell me what the heck “conservation” was. I made a long distance phone call to Jay Krueger, who my uncle told me was a friend of a friend and one of this mysterious breed called “conservators.” It was quite a short conversation, and the upshot was “ask AIC.” I sent away for their brochures (by mail!) and poured over the requirements of the programs. It was the first of many times I turned to AIC to tell me what I needed to do. In graduate school at NYU, the conservation professors referred frequently to the standards and ethics outlined by AIC and required us to follow them in our coursework. I became a member in 1997. As an emerging professional, I found myself moving to Alaska, the home of exactly three conservators: one was a contemporary from the Winterthur/Delaware program (Monica Shah) and the other was the man I had just married (Scott Carroll from the buffalo program, soon to be Carrlee.) I also accepted a job as a curator of collections and exhibits, and began a part-time business doing private conservation work. Suddenly I had a ton of questions about ethics and the standards of practice I would have to live up to in starting a business. Again, I turned to AIC and studied its core documents carefully. I became more interested in listserves in order to stay informed about the conservation world, and frequently thumbed through the AIC directory to see if someone who had posted was affiliated with AIC and therefore steeped in the same professional standards I was familiar with. Occasionally, someone with an excellent reputation and interesting postings was not listed in AIC at all, and I would wonder why. In 2006, I jumped through the hoops to become an AIC Professional Associate, which seemed like the closest thing to being vetted by a national professional conservation organization. I have used AIC and its core documents as a touchstone every step of my career.

After I’d been in the field awhile, I began to hear more about why some people didn’t like AIC. It was elitist, some claimed. Critical and harsh to outsiders. It was behind the times. It didn’t do enough advocacy in the wider public arena to benefit its members. It had a history of excluding natural history, archaeology, and ethnographic conservation. It had a history of setting up confrontational or adversarial relationships with various groups of people: people who were not program trained, restorers, foreigners, archaeologists, maritime conservators, etc. And there were a fair number of people who had been involved with AIC their entire careers but declared they were fed up, and membership in AIC had no benefits for them. At first, I assumed they had just had run-ins with some of the more abrasive and powerful personalities that often dominate organizations like AIC. I daresay conservators can be a cantankerous and self-righteous lot. I still think that’s part of the issue. But I also think there is much to be learned (and perhaps a better path for the future) by studying the history of the organization. There could be a thesis written on that, no doubt. Reading the “Murray Pease Report” and other early documents however, makes it clear that AIC in the 1960’s was largely an organization of conservators specializing in paintings and sculpture. Individual artifacts of high monetary value that justified money being spent on their conservation. Those who identified as “conservators” were interested in developing standards to differentiate themselves from “restorers.” Conservators were scientifically and morally saving art from those who were using dubious recipe books and old wives’ tales to turn a fast buck at the peril of our heritage. Was this the beginning of an “us versus them” mentality? Throughout AIC’s history, the institutional culture has time and again organized itself around fighting “them.” Loosely defined, AIC’s critics have come to see themselves in “them” … anyone who disagrees with the AIC.

WHY DO FOLKS TURN AWAY FROM AIC?

1) They are turned off by a culture of elitism

2) They are round pegs and AIC is a square hole

3) They are not program trained

4) They have unreasonable expectations

5) They are maritime archaeologists (!)

6) They had a run-in with someone irritating who seemed like a mouthpiece for AIC

7) They don’t need the benefits membership offers

Following the recent debate/defeat of certification, it seems that the organization has now entered a period of introspection and re-evaluation. AIC is unlikely to break free of its aura of elitism. It is also doomed to be a venue for those who insist on shooting off their mouths in an undiplomatic fashion. But it does serve a very important role in conservation in the United States: it is our national professional organization. Let’s not underestimate that. But perhaps elitism has been at the root of conservation remaining separate from the museum world: separate programs, training curriculums, and conferences. Chenall’s Nomenclature anyone? Marie Malaro? AAM’s General Facilities Report? Conservation students are not taught what other museum staff do. Often, the conservator on staff is seen as the obstructionist. The one who says “no.” The one who goes by the book and makes everything difficult. The one who does not get invited to the table. Elitism is perhaps the cause of AIC’s biggest failure: no one knows what conservation is. When I give a lab tour, I always have to define conservation. My good friends still mistake me for a curator. Plenty of people think we protect trees. After nearly 50 years (NYU’s Conservation Center was founded in 1960) we still are scarcely known to the public.

As for myself, I feel like I am breaking rank with AIC in some ways. This month, I have joined the AIA and the SAA. As a conservator of ethnographic and archaeological materials, I was not even aware until last week that the SAA has a group about perishables. While I enjoy the AIC annual conference, I think I’ll be aiming to go less often in order to direct resources at attending conferences in allied professions. This has been a talking point in AIC for some time, but there seem to be only a handful who walk the walk. And I am posting information liberally on the internet…info that might have been considered taboo in the past. When I was in graduate school, treatments done as part of the core courses were saved in a file cabinet in the library. But it was locked. Students had to request the key, and it was discouraged. I never found out why, and I was too timid to ask. In some ways, I feel the conservation profession is locked in that way, particularly when it comes to availability of treatment information, lest it “fall into the wrong hands.” After more than a decade in the profession, I have come to believe that in many cases, lack of treatment information does not generally force those objects into the competent hands of conservators. Nor does it mean that the object won’t be treated. People will just give it their best shot. Inside the tent pissing out or outside the tent pissing in?

I have had several stimulating telephone conversations with Jim Jobling at the CRL Texas A&M maritime conservation lab. Certainly there are many ways that his lab is not “AIC compliant.” And you know what? He doesn’t care. He does his work the best he can according to the parallel universe of standards that have developed in maritime conservation world. Google the names of people who treat shipwreck material or wetsite archaeology and most of those names are not coming from the AIC world. In fact, many of those names have been affiliated with the Texas A&M program. Or the program in South Carolina. If AIC cannot or will not be more inclusive then it is up to us. And perhaps our more nimble regional organizations like WAAC and midwest…??MRCG

Elitism is not solely the realm of conservators. There is brand of elitism found among folks who have passion for spending a lot of time with computers. People who are conversant in Blogs, Wikis, Twitter, Ning, Delicious, LinkedIn, Facebook, MySpace…those people are the future. They are connected. They have the answers. Or do they? While the potential of many of these platforms is appealing, the actual content is often rather meagre. Visually stimulating and rather amusing, they remind me of the recent trend toward museums as entertainment. The blockbuster! The wall of graphics! The touch-me interactive! I say, show me the REAL STUFF. Give me content. What is it made of? Who made it? Why?

People who KNOW THINGS tend to share generously, while people who are not sure of their knowledge tend to be defensive and secretive.

Posted by ellencarrlee

Posted by ellencarrlee

Here you are at the registration desk, two floors below the main lobby. Strangely, cell phones still work down here.

Here you are at the registration desk, two floors below the main lobby. Strangely, cell phones still work down here. Can you appreciate how cavernously huge this ballroom is? It even has a sunken terrace area in the center, rather like a 1970’s conversation pit but without the shag rug.

Can you appreciate how cavernously huge this ballroom is? It even has a sunken terrace area in the center, rather like a 1970’s conversation pit but without the shag rug.

The most spacious vendor hall I have ever seen, with plenty of room for everyone, and coffee breaks stationed at each end. So cavernous that those folks bent on bottlenecking the whole thing by standing in chattery groups are utterly thwarted.

The most spacious vendor hall I have ever seen, with plenty of room for everyone, and coffee breaks stationed at each end. So cavernous that those folks bent on bottlenecking the whole thing by standing in chattery groups are utterly thwarted. In the antechamber just behind the vendors was the poster hall…

In the antechamber just behind the vendors was the poster hall…

Typical room at the conference hotel. Unfortunately, internet is not free(it costs about $10 a day, but you’re worth it) and there is no coffee maker in the room. You can order a pot from room service for $9.00 or go to the Starbucks in the lobby. The room does have a nice little balcony with chairs on it, though. And the clock radio has a dock for the iPod I did not bring. Lots of marble in the bathroom.

Typical room at the conference hotel. Unfortunately, internet is not free(it costs about $10 a day, but you’re worth it) and there is no coffee maker in the room. You can order a pot from room service for $9.00 or go to the Starbucks in the lobby. The room does have a nice little balcony with chairs on it, though. And the clock radio has a dock for the iPod I did not bring. Lots of marble in the bathroom.

A professional interest committee of the American Association of Museums. They will be holding what seems to be the first ever PREPARATOR’S CONFERENCE Aug 14-15, 2009 at the Sterling and Francine Clark Museum of Art in Williamstown, Mass.

A professional interest committee of the American Association of Museums. They will be holding what seems to be the first ever PREPARATOR’S CONFERENCE Aug 14-15, 2009 at the Sterling and Francine Clark Museum of Art in Williamstown, Mass. Aprons, chenille weights with plastic pellets, leather weights with lead shot, ear buds, tape measures, water bottles, lab coats…I wonder if they will sell out their inventory of the handmade stuff…

Aprons, chenille weights with plastic pellets, leather weights with lead shot, ear buds, tape measures, water bottles, lab coats…I wonder if they will sell out their inventory of the handmade stuff… How about this?

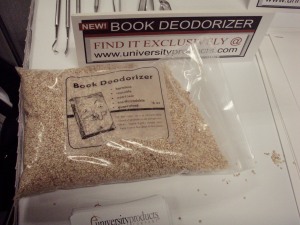

How about this? Hmmmm….this could be handy.

Hmmmm….this could be handy.  Set of acrylic mount-making tools available from University Products

Set of acrylic mount-making tools available from University Products Loved this display of little packets of good stuff from Talas

Loved this display of little packets of good stuff from Talas Check out this cute little visor light that Talas sells!

Check out this cute little visor light that Talas sells! Coveted by anyone crafty who sees one in my lab. Especially wonderful for removal of tape from places it does not belong. But other odd uses too, like opening those maddening little plastic triangle photo mounting corners. I bought one today, my only purchase of the day, for $19.25 and I will gift it to our exhibit designer at the Alaska State Museum…this will save mine from being stolen and also win me some brownie points with the exhibits department…clever clever Ellen.

Coveted by anyone crafty who sees one in my lab. Especially wonderful for removal of tape from places it does not belong. But other odd uses too, like opening those maddening little plastic triangle photo mounting corners. I bought one today, my only purchase of the day, for $19.25 and I will gift it to our exhibit designer at the Alaska State Museum…this will save mine from being stolen and also win me some brownie points with the exhibits department…clever clever Ellen.