On Saturday, June 29 the Chilkat Dye Working Group got together at the museum for some hands-on dye experiments. Here’s some images!

Looking at copper and ammonia dye in a jar on the loading dock of the Alaska State Museum. L to R: Deanna Lampe, Mary Ann Parke, Deb O’Gara, Lily Hope (holding jar), Kay Field Parker, and Liana Wallace.

Ecolana organic undyed merino wool tied in small hanks for testing, and ready to be scoured with Fels Naptha soap. Scouring removes dirt, oils, and contaminants from the wool and hopefully makes the dyeing more successful. I also had hanks that were not scoured for comparison.

Here is Ecolana organic merino wool in small hanks soaking for an hour in distilled water before dyeing. One bowl is the scoured wool, the other is not scoured.

On my back porch, the jar with the yellow liquid is urine with a piece of copper pipe in it. Urine as a chemical has a huge number of traditional uses…dye mordant, cleaning solution, aid in beer making and gunpowder production…google the word “lant” for a rabbit hole of fascination! Aged urine gets more alkaline, eventually having some properties of ammonia, but as you can see the jar on the right (containing ammonia and copper) is far more reactive than the urine on the left, which I don’t think is aged enough. Note the deep cobalt blue color.

Here is a glass pitcher with my copper pipe and ammonia. After a while, there was a white residue, or precipitate, in the bottom of the container as well as some black staining on the inside of the glass near the top of the liquid. When I agitated the solution, it turned this milky blue.

This is Kay Field Parker and her bottle of ammonia with a copper pipe that has been sitting on her porch for more than a year.

Unlike many of the dyes we are using, the ammonia and copper solution is NOT heated (that would produce dangerous fumes). It is used cold. Yarn put in this solution turns a deep steely gray, only slightly blue.

Copper is an important colorant on the Northwest Coast, and the blue greens are the dye color we are looking for. Obviously, this is not what happened to our wool yarn.

On the left is Louet brand merino wool with no color, and then dipped in copper/ammonia. Lily holds some green Louet yarn and what happens when it is dipped in the copper/ammonia.

Patty Fiorella has been experimenting with local plants and the kinds of colors possible. Here she has some sweet gale.

These are nettles, but Patty felt they were not good quality and perhaps it is too late in the season. Using natural dyes means a lot of variables and the results are both art and science.

Here is Patty Fiorella’s dye bath setup, with enamelware pots on hot plates. Aluminum pots are avoided because they might impact the reaction. She boiled the plant material for an hour, strained it out with cheesecloth, let it cool, and put the yarn in to soak up the dye.

Liana Wallace holds a bag of wolf moss (a kind of lichen) and discusses its use with Juneau-Douglas City Museum curator Niko Sanguinetti.

Lily Hope holds some dry wolf moss (top) to compare with the appearance when it has been boiled for an hour in urine. The colorant is now in the dye bath. Yes, there is a bit of an odor. That’s why we are outside!

Kay Field Parker shows us some wool yarn that has been dyed with wolf moss. The deeper yellow on the right has been in the dark for the past 18 years. The lighter, faded yarn is the same yarn, but has been exposed to daylight for a year.

Here are some steel pots on a pancake griddle. The plant material, distilled water, and yarn are all being brought to a boil and heated for an hour together. This is one option for dyeing, but the yarn will have plants bits in it.

Here are more tables with dye baths on burners during this dye session.

Here are two yellows we got this time…on the left is wolf moss (which is a little on the pale side, I have seen it a deeper yellow. Perhaps it was a weak dye bath this time?) On the right is a nice golden yellow made with cow parsnip blossoms in urine. Certainly there were a lot of traditional uses for cow parsnip, so I suspect this color doesn’t last or Chilkat weavers would have perhaps used it more?

Another image of the scene on the loading dock.

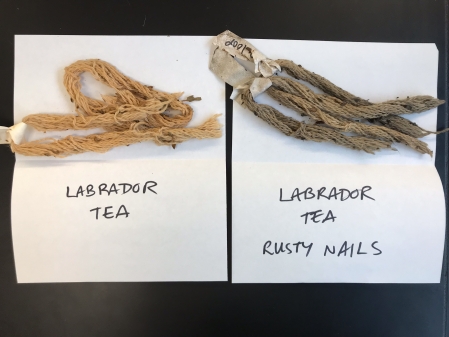

Here are labrador tea leaves Mary Irvine gave me, gathered last year in Sitka. The dye bath smelled lovely, but the resulting color was not very exciting.

The labrador tea with just distilled water gave a weak beige yellow. Adding rusty nail water and nails gives a weak brown. We are looking into the idea of iron as a mordant, but I don’t think this looks so promising.

These were wool yarn samples Kay Field Parker provided from her experimentation with hemlock bark in 2018, and also hemlock bark overdyed with the copper and ammonia solution. These are pretty good dark colors!

A little blurry, but you can see where the nice brown of the hemlock bark dye got much darker in the bottom sample after she dipped it in copper/ammonia.

Kay Field Parker gave me her hemlock dye bath from that 2018 wool dyeing she did, and I thought I’d see if it still worked. NOPE! I guess the dye bath was used up or “exhausted” as they say.

Here’s some yarns drying in the conservation lab after the meeting. I’ve got a few small hanks left I can experiment with next time.

I hung examples of the cow parsnip, copper, and wolf moss in the window (both scoured and unscoured) and put the rest of the hanks in a dark drawer. After a few months exposure, we will see how much fading might happen.

Posted by ellencarrlee

Posted by ellencarrlee

This beaded leather Athabascan vest is the subject of a recent question to the Alaska State Museum: tribal members want to know how to clean leather. The tribe is conducting interviews with members to record the meanings and origins of important regalia and taking photographs. This vest is the Chief’s vest, and still in active use. The tribe does not have a large number of cultural heritage pieces, making it rare and important. Elders still wear items of regalia like this, and some elders may “take them on their journey at their end of this life.” The Cultural Program Manager for the village traditional council is wondering how the normal soiling from years of use might be cleaned, and how they might provide ongoing care for things like this. We need to take into consideration museum care standards but also the cultural need to continue using the vest.

This beaded leather Athabascan vest is the subject of a recent question to the Alaska State Museum: tribal members want to know how to clean leather. The tribe is conducting interviews with members to record the meanings and origins of important regalia and taking photographs. This vest is the Chief’s vest, and still in active use. The tribe does not have a large number of cultural heritage pieces, making it rare and important. Elders still wear items of regalia like this, and some elders may “take them on their journey at their end of this life.” The Cultural Program Manager for the village traditional council is wondering how the normal soiling from years of use might be cleaned, and how they might provide ongoing care for things like this. We need to take into consideration museum care standards but also the cultural need to continue using the vest. So, my photography-loving friends, what are “mammoth plates” and do these count? Glass measures 24″ x 20″ and framed they are 26″ x 22″. They are a lot like lantern slides because they have some sort of emulsion trapped between two sheets of glass and the image is hard to see without light shining through it. But when you do shine the light oh my! Because of their size, the detail and relationship to the viewer is impressive. Are these rare? Is the technique itself compelling? They were cataloged into our collection in the 1960s, and the database suggests they are “dry plate” or “transparency” but I’m not sure those are the correct terms for the photographic process used.

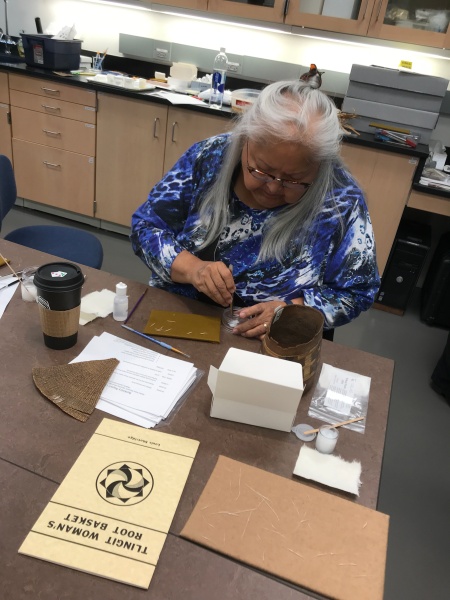

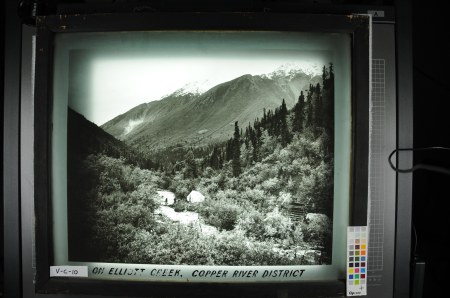

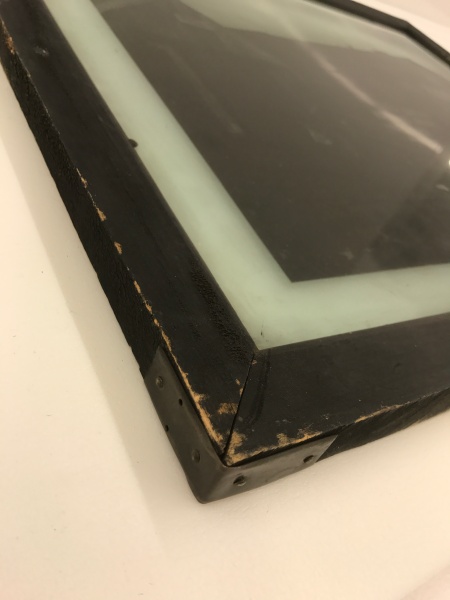

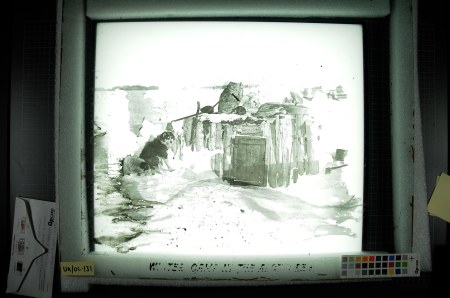

So, my photography-loving friends, what are “mammoth plates” and do these count? Glass measures 24″ x 20″ and framed they are 26″ x 22″. They are a lot like lantern slides because they have some sort of emulsion trapped between two sheets of glass and the image is hard to see without light shining through it. But when you do shine the light oh my! Because of their size, the detail and relationship to the viewer is impressive. Are these rare? Is the technique itself compelling? They were cataloged into our collection in the 1960s, and the database suggests they are “dry plate” or “transparency” but I’m not sure those are the correct terms for the photographic process used.

This posting is a gift for a certain clan caretaker and woodworker who is interested in making some of these chests. It is easy to find photos of the exterior. This post is heavy on the visuals and interiors, to help understand the construction technique.

This posting is a gift for a certain clan caretaker and woodworker who is interested in making some of these chests. It is easy to find photos of the exterior. This post is heavy on the visuals and interiors, to help understand the construction technique.